Radha Krishan Industries vs. State Of Himachal Pradesh And Others

(Sc (Supreme Court), N/A)

A Factual Background

B Submissions

B.1 Maintainability of the writ petition before the High Court

B.2 Challenge on merits: improper invocation of Section 83

C Legal Position

C.1 Maintainability of writ petition before the High Court

C.2 Provisional Attachment

C.3 Delegation of authority under CGST Act

D Analysis

E Summary of findings

A Factual Background

1 This appeal raises significant issues of public importance, engaging as it does, the interface between citizens and their businesses with the fiscal administration. Legislation enacted for the levy of goods and services tax confers a power on the taxation authorities to impose a provisional attachment on the properties of the assessee, including bank accounts. The legislation in Himachal Pradesh, which comes up for interpretation in the present case, has conferred the power on the Commissioner to order provisional attachment of the property of the assessee, subject to the formation of an opinion that such attachment is necessary in the interest of protecting the government revenue. What specifically, is the ambit of this power? What are the safeguards available to the citizen? In interpreting the law, the court has to chart a course which will ensure a fair exercise of statutory powers. The legitimate concerns of citizens over arbitrary exercises of power have to be protected while ensuring that the legislative purpose in entrusting the authority to order a provisional attachment is fulfilled.

The rule of law in a constitutional framework is fulfilled when law is substantively fair, procedurally fair and applied in a fair manner. Each of these three components will need to be addressed in the course of interpreting the tax statute in the present case.

2 This appeal arises from a judgment and order dated 1 January 2021 of a Division Bench of the High Court of Himachal Pradesh. The High Court dismissed the writ petition instituted under Article 226 of the Constitution challenging orders of provisional attachment on the ground that an alternate remedy is available.

The appellant challenged the orders issued on 28 October 2020 by the Joint Commissioner of State Taxes and Excise, Parwanoo “third respondent” provisionally attaching the appellant’s receivables from its customers. The provisional attachment was ordered while invoking Section 83 of the Himachal Pradesh Goods and Service Tax Act, 2017 “HPGST Act” and Rule 159 of Himachal Pradesh Goods and Service Tax Rules, 2017 “HPGST Rules”. While dismissing the writ petition on grounds of maintainability the High Court was of the view that the appellant had an ‘alternative and efficacious remedy’ of an appeal under Section 107 of the HPGST Act.

3 At issue in this case is whether the orders of provisional attachment issued by the third respondent against the appellant on 28 October 2020 are in consonance with the conditions stipulated in Section 83 of the HPGST Act. The answer to this will require the court to embark on an interpretative journey of unravelling the substantive and procedural content of the power. The preliminary issue is whether the High Court was right in concluding that the provisional attachment could not be challenged in a petition under Article 226.

4 The facts in the context of which this case arises are thus: the appellant manufactures lead according to the specific requirements of its clients, and has a factory at village Meerpur Gurudwara, Kala-Amb in the District of Sirmaur of Himachal Pradesh. The appellant has been in the same line of business since 2008. Upon the introduction of the Goods and Services tax “GST”, the appellant migrated to and was registered under GST - GSTIN No. O2AAKFR7402H2ZE - with effect from 1 July 2017.

5 On 3 October 2018, a notice (The respondents before this Court have stated that the said document was in fact a memo under Section 70 of HPGST Act and not a show cause notice, and it was inadvertently mentioned that it was a notice issued under Section 74 of the HPGST Act.) was issued to the appellant under Section 74 of the HPGST Act and the Central Goods and Services Tax Act (“CGST Act”) by the third respondent requiring it to appear on 9 October 2018 and produce (i) invoices pertaining to inward and outward supplies for the yea₹ 2017-18 and 2018-19; (ii) party-wise summary/ledger of inward supplies; (iii) proof of payment of GST with a commodity-wise breakup; and (iv) copies of GSTR-1, GSTR-2 and GSTR-3 returns from July 2017 to July 2018. The appellant appeared before the third respondent and submitted original tax invoices pertaining to inward and outward supplies for 2017-18 and 2018-19 by a letter dated 15 October 2018.

6 On 10 October 2018, a ‘detection case’ was registered against GM Powertech, Kala-Amb (“GM Powertech”), one of the suppliers of the appellant, under Section 74 of the HPGST Act and the CGST Act read with Section 20 of the Integrated Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017 (“IGST Act”). This was through a search and seizure under Section 67 of the HPGST Act and CGST Act. The partners of GM Powertech were arrested on 3 December 2018 on the ground of raising fraudulent claims of input tax credit (“ITC”) from fake/fictitious firms in Delhi and Kanpur.

7 The appellant received a memo by an e-mail dated 15 December 2018 from the third respondent directing it to be present on 17 December 2018 for explaining the allegedly illegal claim of ITC made during 2017-18 and 2018-19. By its letter dated 17 December 2018, the appellant contended that it had validly claimed ITC as it fulfilled the conditions under Section 16 and other provisions of the HPGST Act and the CGST Act.

8 On 9 January 2019, a notice (“SCN”) was issued to Fujikawa Power, Bagbania, BBN Baddi, one of the customers of the appellant, for provisionally attaching an amount of ₹ 5 crores due to the appellant, under Section 83 of the HPGST Act.

On 19 January 2019, the third respondent passed an order of provisional attachment in respect of receivables worth ₹ 5 crores due from Fujikawa Power. This order inadvertently referred to Sarika Industries instead of the appellant. The appellant responded by a representation dated 29 January 2019, claiming inter alia, that the order of attachment was without affording a hearing.

The appellant also claimed that on 26 December 2018, they had noticed that the ITC had been blocked without prior notice. On 30 January 2019, the notice of attachment was withdrawn by the third respondent.

9 According to the respondents, after the case of GM Powertech was investigated, tax evasion was detected. GM Powertech was found to have claimed and utilized ITC against invoices issued by “fake fictitious firms without actual movement of goods…” GM Powertech had issued invoices to various recipients in Himachal Pradesh including the appellant. On 4 July 2020, the third respondent issued an intimation to the appellant under Section 74(5) of the HPGST Act of tax ascertained as being payable (Form GST DRC-01A), advising it to pay tax, interest and penalty of ₹ 5.03 crores. The appellant was given an opportunity to file its submissions against the ascertainment of the amount by 4 August 2020.

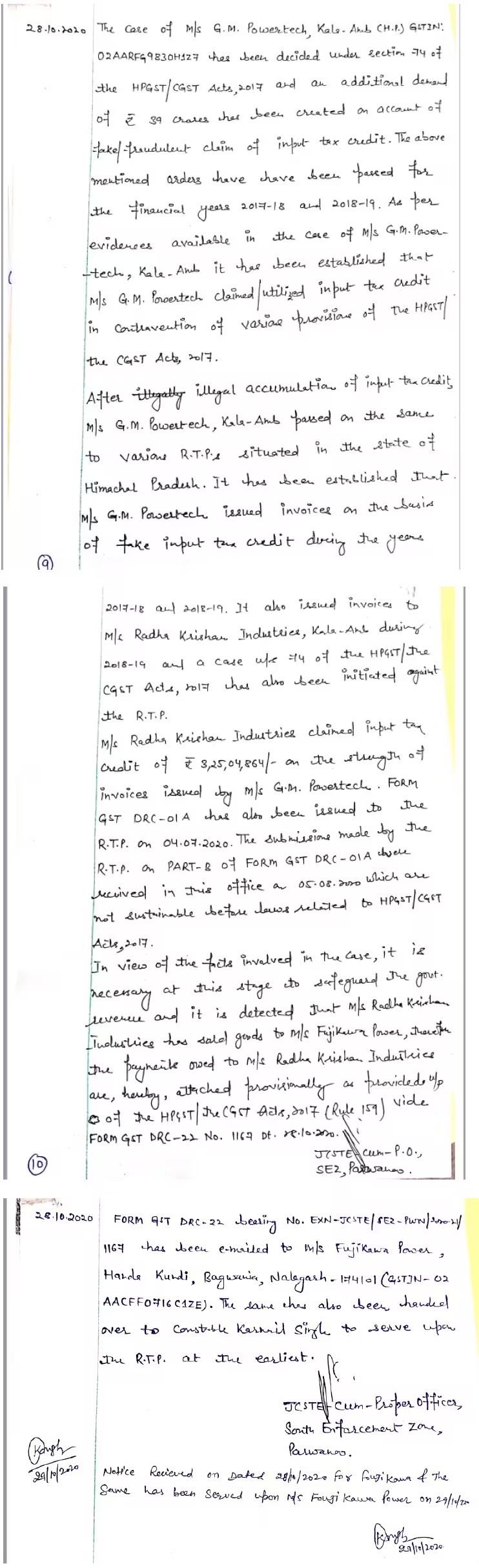

10 A tax liability of ₹ 39.48 crores was confirmed against GM Powertech on the conclusion of the proceedings against it. GM Powertech was found to have no business establishment or property in Himachal Pradesh and the case was considered to fall into the category of a serious tax fraud.

11 On 21 October 2020, the Commissioner of State Taxes and Excise, Himachal Pradesh (“second respondent/Commissioner”) delegated his powers under Section 83 of the HPGST Act to the third respondent. In exercise of the powers delegated by the Commissioner, the third respondent issued two orders of provisional attachment DRC-22 vide Memo No EXN-JCSTE/SEZParwanoo/2020-21/1171 and EXN-JCSTE/SEZ Parwanoo/2020-21/1167 (“orders of provisional attachment”) dated 28 October 2020 attaching the receivables of the appellant from its customers, Fujikawa Power and M/s Deepak International. The attachment order issued to Fujikawa Power under Rule 159(1) of the HPGST Rules noted that it owed about ₹ 4 crores to the appellant. The order states that the appellant was found to be involved in an ITC fraud amounting to ₹ 5,03,82,554/- (₹ 5.03 crores) during 2017-18 and 2018-19. The order, in its relevant part, provides:

“In order to protect the interests of revenue and in exercise of the powers conferred/delegated by Commissioner of the State Taxes & Excise, HP vide office order No.12-4/78-EXN-Tax-Part-278/22(a)- 26780-82 dated 21.10.2020 under section 83 of the Act, I, U.S. Rana, Joint Commissioner of State Taxes & Excise, South Enforcement Zone, Parwanoo, hereby provisionally attach the payment to the extent of ₹ 5,03,82,554/- of M/s Radha Krishan Industries, Kala-Amb. Henceforth, no payment shall be allowed to be made from your company to M/s RadhaKrishan Industries without the prior permission of this department / office.”

A similar order was issued to Deepak International, noting that a payment of ₹ 2.91 crores was owed by it to the appellant.

12 On 4 November 2020, the appellant filed a representation and objections against the attachment and denied liability. By an order dated 6 November 2020, the third respondent rejected the objections of the appellant. The third respondent stated that collectively payments “only” worth ₹ 4.92 crores from both of the appellant’s customers were attached.

13 On 27 November 2020, the third respondent issued a notice to show cause to the appellant under Section 74(1) of the HPGST Act for recovering the ITC, interest and penalty. The notice was issued on the basis that the appellant had claimed ITC on the supplies received from GM Powertech and since the inward supplies made by GM Powertech were found to be fake, the appellant’s claim of ITC was also in question.

14 The orders of provisional attachment and the order passed by the Commissioner on 21 October 2020 delegating his powers under Section 83 of the HPGST Act to the third respondent, were challenged by the appellant before the High Court in a writ petition (Writ Petition No. 5648 of 2020) under Article 226.

15 While dismissing the writ petition, the High Court held that it was undisputed that the third respondent and the Divisional Commissioner, who has been appointed as Commissioner (Appeals) under the GST Act, are constituted under the HPGST Act, and therefore, it is assumed that there is no illegal or irregular exercise of jurisdiction. The High Court further observed that even if there is some defect in the procedure followed during the hearing of the case, it does not follow that the authority acted without jurisdiction, and though the order may be irregular or defective, it cannot be a nullity so long it has been passed by the competent authority.

16 The High Court held that a writ is ordinarily not maintainable when there exists an alternative remedy. The exceptions to this rule are where the statutory authority has not acted in accordance with the provisions of the legislation; or acted in defiance of the fundamental principles of judicial procedure or where an order has been passed in violation of the principles of natural justice. The High Court held that it would not entertain a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution, if an efficacious remedy is available to the aggrieved person or where the statute under which the action complained of has been taken contains a mechanism for redressal of grievances. The High Court held that when a statutory forum of appeal exists, an appeal should “not be entertained ignoring the statutory dispensation”.

17 Noting that the appellant has an alternative and efficacious remedy of appeal under Section 107 of the HPGST Act, the High Court refused to entertain the writ petition. The High Court held that it was fortified in this view by the fact that the writ petition filed by GM Powertech, has also not been entertained and that it has been relegated to avail of the alternative remedy.

18 Subsequent to the dismissal of the writ petition by the High Court, certain developments have taken place. On 12 January 2021, the appellant sought to inspect the files for GM Powertech and stated that no documents in this regard had been provided to it in context of the proceedings initiated under Section 74.

In response, the third respondent allowed the appellant to inspect the contents of the appellant’s case file. According to the respondent, the appellant failed to exercise this option and did not reply to the show cause notice dated 27 November 2020. Thereafter, on 18 February 2021, an order under Section 74(9) of the HPGST Act was passed by the third respondent confirming a tax demand of ₹ 8,30,27,218. This order under Section 74(9) has been assailed by the appellant before the appellate authority under Section 107. The dismissal of the petition challenging the orders of provisional attachment is in question in the present proceedings.

B Submissions

19 Mr Puneet Bali, learned senior counsel appearing on behalf of the appellant addressed the following submissions:

B.1 Maintainability of the writ petition before the High Court:

(i) No efficacious alternative remedy is available against the orders of provisional attachment passed under Section 83 of the HPGST Act. The jurisdiction to pass an order under Section 83 is conferred on the Commissioner of State Taxes. Although the power stands delegated to the third respondent, the order is still deemed to be passed by the Commissioner (second respondent). Under the GST Act, an appeal against the order of the Commissioner lies before the GST Appellate Tribunal which has not been constituted till date. Thus, the only remedy available to the appellant was by filing a writ petition;

(ii) Reliance was placed on Whirlpool Corporation v Registrar of Trademarks, Mumbai (1998) 8 SCC 1 to argue that an alternative remedy is not a bar to the exercise of the writ jurisdiction of the High Court if the writ petition is filed for enforcement of fundamental rights; where there has been a violation of the principles of natural justice; where the order or the proceedings are wholly without jurisdiction; or when the vires of an Act is challenged;

(iii) The third respondent had withdrawn the earlier orders of provisional attachment issued in January 2019 after considering the representation filed by the appellant. The impugned orders of provisional attachment were issued on 28 October 2020, on the same set of facts and allegations. Thus, the impugned orders of provisional attachment amount to a review of the earlier orders by the same respondent, which is contrary to the HPGST Act, as it does not provide for powers of review;

(iv) The impugned orders of provisional attachment are in violation of the procedure established under sub-rule (5) of Rule 159 of HPGST Rules, which provides that an opportunity of being heard is to be given against the provisional attachment as a mandatory requirement. In this case, the appellant filed objections to the orders of provisional attachment on 4 November 2020 and the objections were rejected by the third respondent on 6 November 2020, without providing an opportunity of being heard to the appellant;

(v) The reliance placed by the High Court on the judgment in the case of GM Powertech and others v State of H.P CWP No. 5462 of 2020 to state that a similar petition was not entertained is misplaced. In that case, GM Powertech had challenged the order of assessment in the writ petition, while the appellant has challenged the orders of provisional attachment made prior to the assessment. Additionally, the case of GM Powertech did not fall within the exceptions to the rule of alternate remedy;

(vi) The High Courts should not have dismissed the writ petition on grounds of maintainability if the facts of the case are not disputed by the State as held in Rajasthan State Electricity Board v Union of India 2008 (5) SCC 632; and

(vii) Reliance was placed on Calcutta Discount Co. Ltd. v Income Tax Officer, Companies District I, Calcutta AIR 1961 SC 372 and Commissioner of Income Tax, Gujarat v M/s A Raman and Co. AIR 1968 SC 49 to argue that the High Court can exercise its powers under Article 226 of the Constitution to issue an order prohibiting the tax officer from proceedings to assess the liability, if the conditions precedent to the exercise of such jurisdiction have not been met.

B.2 Challenge on merits: improper invocation of Section 83

(i) The power of provisional attachment under Section 83 of the HPGST Act is a drastic power and must be exercised with extreme care and caution;

(ii) The power under Section 83 of the HPGST Act cannot be exercised unless there is sufficient material on record to justify that the assessee is about to dispose of the whole or part of its property to thwart the ultimate collection of tax;

(iii) The existence of relevant material is a pre-condition to the formation of an opinion by the Commissioner;

(iv) The third respondent failed to show any material on record to indicate that the appellant is a “fly by night operator” or is disposing off assets to defeat the collection of tax;

(v) The stated reason for provisional attachment - the initiation of proceedings and passing of an order under Section 74 against the appellant’s supplier, GM Powertech - is insufficient to invoke the powers of provisional attachment against the appellant;

(vi) The third respondent has failed to show that there is a threat to the interests of the revenue on account of the appellant’s alleged involvement in the said ITC fraud of GM Powertech;

(vii) The appellant has paid an output tax of ₹ 12,49,90,267.14 (₹ 12.49 crores) for the relevant period, which is more than the ITC of ₹ 3.25 crores which the appellant has allegedly taken fraudulently;

(viii) Even if the revenue has to attach the properties of the assessee, immovable properties must be attached. Attachment of bank accounts and trading assets should be a last resort only as it paralyses the business of the assessee;

(ix) The pendency of proceedings under Sections 62, 63, 64, 67, 73 or 74, of the HPGST Act, is a pre-condition for invoking the provisions of Section 83 of the HPGST Act;

(x) The provisional attachment of the appellant’s assets was made on 28 October 2020, before the proceedings were initiated against the appellant under Section 74 of the HPGST Act on 27 November 2020. Thus, the provisional attachment was made without jurisdiction and in violation of Section 83;

(xi) The provisions of Section 83 of the HPGST Act do not provide for making provisional attachment a second time, once the first attachment is withdrawn. Moreover, the HPGST Act, does not provide the third respondent the power of review to review his earlier decision regarding provisional attachment;

(xii) The first provisional attachment against the appellant was “withdrawn completely with immediate effect” in January 2019 and the same had gained finality. Thus, the impugned orders of provisional attachment for the second time, are without the authority of law and should be set aside;

(xiii) Provisional attachment of 100% of the alleged amount is not permissible as per law;

(xiv) While Section 83 of the HPGST Act does not provide for the percentage of alleged amount to be attached, the powers under this section must be guided by other provisions of the Act;

(xv) Under Section 74 of the HPGST Act, once the tax demand becomes payable, an assessee can only challenge this demand in appeal after depositing 10% of the disputed amount and the remaining demand is stayed. In contrast, the provisional attachment of 100% of the alleged amount even before the finalisation of the tax demand is contrary to the legislative intent;

(xvi) The third respondent has taken a contradictory stand with respect to collection of tax from the appellant. Even if it is admitted that the transaction between the appellant and GM Powertech was a fake transaction without actual movement of goods, it follows that the appellant cannot claim refund of ITC and nor would the appellant be liable to pay tax on outward supplies. However, the appellant has already paid ₹ 12.49 crores of tax on outward supplies;

(xvii) The third respondent has raised a demand of ₹ 39 crores against GM Powertech for illegally availing ITC. Once the tax demand has been confirmed against GM Powertech, refusal to grant ITC to the appellant would amount to double collection of tax.

20 Opposing these submissions, Mr Akshay Amritanshu, learned counsel appearing on behalf of the State of Himachal Pradesh, submitted that:

(i) The SLP should be dismissed as the appellant has an alternate and efficacious remedy of an appeal under Section 107 of the HPGST Act. Moreover, the SLP has been rendered infructuous due to the order dated 18 February 2021 under Section 74(9) of the HPGST Act and the consequent appeal filed by the appellant against this order before the appellate authority;

(ii) In paragraph 4 of the impugned judgment, it has been noted that the appellant had admitted that it had an alternative remedy by way of an appeal under Section 107 of the HPGST Act;

(iii) The delegation of powers under Section 83 of the HPGST Act by the second respondent to the third respondent does not imply that there was an irregular or illegal exercise of jurisdiction by the second respondent;

(iv) The order under Section 74(9) against GM Powertech has not been challenged and has gained finality. Since it has been found that all purchases of GM Powertech were fraudulent, there could have been no outward sale to the appellant. Thus, the transaction between GM Powertech and appellant would also be fraudulent;

(v) The orders of provisional attachment were issued after the proceedings against GM Powertech had concluded;

(vi) GM Powertech had no property or business establishment in Himachal Pradesh. In order to avoid a similar situation against the appellant and to protect the interests of revenue, the impugned orders of provisional attachment were passed;

(vii) The proceedings of provisional attachment under Section 83 of the HPGST Act had concluded after rejection of the objections filed by the appellant on 6 November 2020. The appellant participated in these proceedings and did not challenge the orders of provisional attachment. Thus, the appellant is estopped from challenging the initiation of proceedings under Section 83 of the HPGST Act;

(viii) The impugned orders of provisional attachment were based on a fresh set of allegations, after the proceedings against GM Powertech had been concluded and it was found that GM Powertech had no business or properties in Himachal Pradesh;

(ix) After the appellant filed objections to the orders of provisional attachment, it was in the discretion of the Commissioner whether or not to grant an opportunity of a hearing to the appellant;

(x) Merely because the appellant has paid ₹ 12 crores of tax, does not imply that the appellant did not engage in the ITC fraud;

(xi) There was no violation of the principles of natural justice as an order of provisional attachment does not require a prior notice to be issued to the assessee;

(xii) The necessary prerequisites for triggering Section 83 of the HPGST Act were complied with;

(xiii) The appellant had not sought any prior stay on the orders of provisional attachment and thus, it is not conceivable that the business of the appellant has become paralyzed due to these orders;

(xiv) The provisional attachment is not only for the purpose of recovery, but is intended to safeguard the interests of the revenue while the proceedings are pending; and

(xv) The legislature did not provide any quantum or percentage for the purpose of provisional attachment under Section 83 of the Act. Thus, a comparison with other provisions of the HPGST Act, including Section 107, is incorrect.

C Legal Position

21 The following issues arise in the present case:

(i) Whether a writ petition challenging the orders of provisional attachment was maintainable under Article 226 of the Constitution before the High Court; and

(ii) If the answer to (i) is in the affirmative, whether the orders of provisional attachment constitute a valid exercise of power.

22 The appellant has advanced submissions on and adverted to the merits of the proceedings initiated under Section 74 of the HPGST Act. The order dated 18 February 2021 under Section 74 (9) of the HPGST Act is not in challenge before this Court. An appeal against the order is pending before the appellate authority under Section 107 of the HPGST Act. We will not adjudicate upon the merits of the order under section 74(9). This judgment is confined to the two issues formulated above.

23 We shall now review the position of law on the questions before us.

C.1 Maintainability of writ petition before the High Court

24 The High Court has dealt with the maintainability of the petition under Article 226 of the Constitution. Relying on the decision of this Court in Assistant Commissioner (CT) LTU, Kakinada and others v Glaxo Smith Kline Consumer Health Care Limited AIR 2020 SC 2819, the High Court noted that although it can entertain a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution, it must not do so when the aggrieved person has an effective alternate remedy available in law.

However, certain exceptions to this “rule of alternate remedy” include where, the statutory authority has not acted in accordance with the provisions of the law or acted in defiance of the fundamental principles of judicial procedure; or has resorted to invoke provisions, which are repealed; or where an order has been passed in violation of the principles of natural justice. Applying this formulation, the High Court noted that the appellant has an alternate remedy available under the GST Act and thus, the petition was not maintainable.

25 In this background, it becomes necessary for this Court, to dwell on the “rule of alternate remedy” and its judicial exposition. In Whirlpool Corporation v Registrar of Trademarks, Mumbai (1998) 8 SCC 1 (“Whirlpool”), a two judge Bench of this Court after reviewing the case law on this point, noted:

“14. The power to issue prerogative writs under Article 226 of the Constitution is plenary in nature and is not limited by any other provision of the Constitution. This power can be exercised by the High Court not only for issuing writs in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari for the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights contained in Part III of the Constitution but also for “any other purpose”.

15. Under Article 226 of the Constitution, the High Court, having regard to the facts of the case, has a discretion to entertain or not to entertain a writ petition. But the High Court has imposed upon itself certain restrictions one of which is that if an effective and efficacious remedy is available, the High Court would not normally exercise its jurisdiction. But the alternative remedy has been consistently held by this Court not to operate as a bar in at least three contingencies, namely, where the writ petition has been filed for the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights or where there has been a violation of the principle of natural justice or where the order or proceedings are wholly without jurisdiction or the vires of an Act is challenged. There is a plethora of case-law on this point but to cut down this circle of forensic whirlpool, we would rely on some old decisions of the evolutionary era of the constitutional law as they still hold the field.”

(emphasis supplied)

26 Following the dictum of this Court in Whirlpool (supra), in Harbanslal Sahnia v Indian Oil Corpn. Ltd. (2003) 2 SCC 107, this court noted that

“7. So far as the view taken by the High Court that the remedy by way of recourse to arbitration clause was available to the appellants and therefore the writ petition filed by the appellants was liable to be dismissed is concerned, suffice it to observe that the rule of exclusion of writ jurisdiction by availability of an alternative remedy is a rule of discretion and not one of compulsion. In an appropriate case, in spite of availability of the alternative remedy, the High Court may still exercise its writ jurisdiction in at least three contingencies: (i) where the writ petition seeks enforcement of any of the fundamental rights; (ii) where there is failure of principles of natural justice; or (iii) where the orders or proceedings are wholly without jurisdiction or the vires of an Act is challenged. (See Whirlpool Corpn. v. Registrar of Trade Marks [(1998) 8 SCC 1] .) The present case attracts applicability of the first two contingencies. Moreover, as noted, the appellants' dealership, which is their bread and butter, came to be terminated for an irrelevant and non-existent cause. In such circumstances, we feel that the appellants should have been allowed relief by the High Court itself instead of driving them to the need of initiating arbitration proceedings.” (emphasis supplied)

27 The principles of law which emerge are that :

(i) The power under Article 226 of the Constitution to issue writs can be exercised not only for the enforcement of fundamental rights, but for any other purpose as well;

(ii) The High Court has the discretion not to entertain a writ petition. One of the restrictions placed on the power of the High Court is where an effective alternate remedy is available to the aggrieved person;

(iii) Exceptions to the rule of alternate remedy arise where (a) the writ petition has been filed for the enforcement of a fundamental right protected by Part III of the Constitution; (b) there has been a violation of the principles of natural justice; (c) the order or proceedings are wholly without jurisdiction; or (d) the vires of a legislation is challenged;

(iv) An alternate remedy by itself does not divest the High Court of its powers under Article 226 of the Constitution in an appropriate case though ordinarily, a writ petition should not be entertained when an efficacious alternate remedy is provided by law;

(v) When a right is created by a statute, which itself prescribes the remedy or procedure for enforcing the right or liability, resort must be had to that particular statutory remedy before invoking the discretionary remedy under Article 226 of the Constitution. This rule of exhaustion of statutory remedies is a rule of policy, convenience and discretion; and

(vi) In cases where there are disputed questions of fact, the High Court may decide to decline jurisdiction in a writ petition. However, if the High Court is objectively of the view that the nature of the controversy requires the exercise of its writ jurisdiction, such a view would not readily be interfered with.

28 These principles have been consistently upheld by this Court in Seth Chand Ratan v Pandit Durga Prasad (2003) 5 SCC 399, Babubhai Muljibhai Patel v Nandlal Khodidas Barot (1974) 2 SCC 706 and Rajasthan SEB v. Union of India, (2008) 5 SCC 632 among other decisions.

C.2 Provisional Attachment

29 At this stage, we will advert to relevant precedents outlining the contours of the power of provisional attachment and specifically, in the context of provisions worded similarly to Section 83 of the HPGST Act.

30 The decision of this Court in Raman Tech Process Engg Co and Anr v Solanki Traders 2008(1) R.C.R.(Civil) 195 was concerned with the power of a civil court under Order 38 Rule 5 of the CPC to order an attachment before judgment. In that case, proceedings had been instituted by the respondent, for the recovery of moneys due for the supply of material to the appellant. The plaintiff moved an application under Order 38 Rule 5, for a direction to the defendants to furnish security for the suit claim and if they failed to do so, for attachment before judgment. This Court described the power of attachment before judgment in the following terms:

“5. The power under Order 38, Rule 5 Civil Procedure Code is a drastic and extraordinary power. Such power should not be exercised mechanically or merely for the asking. It should be used sparingly and strictly in accordance with the Rule. The purpose of Order 38, Rule 5 not to convert an unsecured debt into a secured debt. Any attempt by a plaintiff to utilize the provisions of Order 38 Rule 5 as a leverage for coercing the defendant to settle the suit claim should be discouraged.

Instances are not wanting where bloated and doubtful claims are realized by unscrupulous plaintiffs, by obtaining orders of attachment before judgment and forcing the defendants for out of court settlements, under threat of attachment.

6. A defendant is not debarred from dealing with his property merely because a suit is filed or about to be filed against him.

Shifting of business from one premises to another premises or removal of machinery to another premises by itself is not a ground for granting attachment before judgment. A plaintiff should show, prima facie, that his claim is bona fide and valid and also satisfy the court that the defendant is about to remove or dispose of the whole or part of his property, with the intention of obstructing or delaying the execution of any decree that may be passed against him, before power is exercised under Order 38, Rule 5 CPC. Courts should also keep in view the principles relating to grant of attachment before judgment [internal citation omitted].”

31 A body of precedent has emerged in the High Courts on the exercise of the power under Section 83 of the CGST Act (akin to the State GST Act “SGST Act”). The shared learning which emerges from these decisions of the High Court needs recognition. In Valerius Industries v Union of India 2019 (30) GSTL 15 (Gujarat), the Gujarat High Court laid down the principles for the construction of Section 83 of the SGST/CGST Act. The High Court noted that a provisional attachment on the basis of a subjective satisfaction, absent any cogent or credible material, constitutes malice in law. It further outlined the principles for the exercise of the power:

“52. […]

The order of provisional attachment before the assessment order is made, may be justified if the assessing authority or any other authority empowered in law is of the opinion that it is necessary to protect the interest of revenue. However, the subjective satisfaction should be based on some credible materials or information…It is not any and every material, howsoever vague and indefinite or distant, remote or far-fetching, which would warrant the formation of the belief.

(1) The power conferred upon the authority under Section 83 of the Act for provisional attachment could be termed as a very drastic and far-reaching power. Such power should be used sparingly and only on substantive weighty grounds and reasons.

(3) The power of provisional attachment under Section 83 of the Act should be exercised by the authority only if there is a reasonable apprehension that the assessee may default the ultimate collection of the demand that is likely to be raised on completion of the assessment. It should, therefore, be exercised with extreme care and caution.

(4) The power under Section 83 of the Act for provisional attachment should be exercised only if there is sufficient material on record to justify the satisfaction that the assessee is about to dispose of wholly or any part of his/her property with a view to thwarting the ultimate collection of demand and in order to achieve the said objective, the attachment should be of the properties and to that extent, it is required to achieve this objective.

(5) The power under Section 83 of the Act should neither be used as a tool to harass the assessee nor should it be used in a manner which may have an irreversible detrimental effect on the business of the assessee.

(6) The attachment of bank account and trading assets should be resorted to only as a last resort or measure. The provisional attachment under Section 83 of the Act should not be equated with the attachment in the course of the recovery proceedings.

(7) The authority before exercising power under Section 83 of the Act for provisional attachment should take into consideration two things:

(i) whether it is a revenue neutral situation.

(ii) the statement of “output liability or input credit”. Having regard to the amount paid by reversing the input tax credit if the interest of the revenue is sufficiently secured, then the authority may not be justified in invoking its power under Section 83 of the Act for the purpose of provisional attachment.” (emphasis supplied)

32 In the same vein, in Jai Ambey Filament Pvt Ltd v Union of India 2021 (44) GSTL 41 (Gujarat), the Gujarat High Court reiterated that the subjective satisfaction as to the need for provisional attachment must be based on credible information that the attachment is necessary. This opinion cannot be formed based on “imaginary grounds, wishful thinking, howsoever laudable that may be.” The High Court further held, that on his opinion being challenged, the competent officer must be able to show the material on the basis of which the belief is formed.

33 In Patran Steel Rolling Mill v Assistant Commissioner of State Tax Unit 2 2019 (20) GSTL 732 (Gujarat), the Gujarat High Court cited two instances in which provisional attachment would be apposite, these being where the assessee is a ‘fly by night operator’ and if the assessee will not be able to pay its dues after assessment.

34 Similar to the decisions of the Gujarat High Court, other High Courts have recognized the restrictive nature of the power of provisional attachment under Section 83 of the SGST Act and the need for it to be based on adequate substantive material. The High Courts have also underscored the extraordinary nature of this power, necessitating due caution in its exercise. (Bindal Smelting Private Limited v Addl. Director General of GST Intelligence, 2020 (34 G.S.T.L 592 (P&H); Society for Integrated Development of Urban and Rural Areas v Commissioner of Income Tax, A.P. II, Hyd, 2001 (252) ITR 642; Vinod Kumar Murlidhar Prop. Of Chechani Trading Co v. State of Gujarat, Special Civil Application No. 12498 of 2020 dated 9 December 2020)

35 The Delhi High Court, in Proex Fashion Private Limited v Government of India WP(C) 11245 of 2020 dated 6 January 2021 outlined the following statutorily stipulated conditions for the invocation of Section 83 of the SGST Act:

“i) Order should be passed by Commissioner;

ii) Proceeding under Section 62 or 63 or 64 or 67 or 73 or 74 should be pending;

iii) Commissioner must form an opinion;

iv) Order should be passed to protect interest of revenue;

v) It must be necessary to attach property.”

36 In UFV India Global Education v Union of India 2020 (43) GSTL 472, the Punjab and Haryana High Court held that pendency of proceedings under the sections mentioned in Section 83 viz. Sections 62 or 63 or 64 or 67 or 73 or 74 is the sine qua non for an order of provisional attachment to be issued under Section 83.

37 Another case which is relevant for our purposes is the decision of the Bombay High Court in Kaish Impex Private Limited v Union of India (2020) 6 AIR Bom R 122. In this case, the taxation authorities were enquiring into fraudulent claiming of ITC on the basis of fictitious transactions by an export firm in Delhi, against whom proceedings under Section 67 of the CGST Act had been initiated. On tracing the money trail, the petitioner was summoned under Section 70 of the CGST Act and his bank accounts were provisionally attached under Section 83 of the CGST Act. On dealing with the question of whether the bank accounts of the petitioner could be attached, when there were no pending proceedings against him and proceedings were pending against another taxable entity, the High Court held that the proceedings referred to under Section 83 of the Act must be pending against the taxable entity whose property is being attached. The High Court noted that:

“18. […] Section 83 though uses the phrase ‘pendency of any proceedings’, the proceedings are referable to section 62, 63, 64, 67, 73 and 74 of the Act and none other. The bank account of the taxable person can be attached against whom the proceedings under the sections mentioned above are initiated. Section 83 does not provide for an automatic extension to any other taxable person from an inquiry specifically launched against a taxable person under these provisions. Section 83 read with section 159(2), and the form GST DRC-22 show that a proceeding has to be initiated against a specific taxable person, an opinion has to be formed that to protect the interest of Revenue an order of provisional attachment is necessary. The format of the order, i.e. the form GST DRC-22 also specifies the particulars of a registered taxable person and which proceedings have been launched against the aforesaid taxable person indicating a nexus between the proceedings to be initiated against a taxable person and provisional attachment of bank account of such taxable person.” (emphasis supplied)

C.3 Delegation of authority under CGST Act

38 The learned counsel for the respondent State, during the course of his submissions, has also sought to justify the delegation of powers by the Commissioner to the Joint Commissioner by way of the impugned notification dated 21 October 2020 for the purpose of attachment of properties under Section 83 of the HPGST Act. In this regard, reliance was placed on Nathanlal Maganlal Chauhan v State of Gujarat, 2020 SCC Online Guj 1811 where the Gujarat High Court was considering the validity of a notification by which the Commissioner of State Tax had delegated all the functions under the SGST Act to the Special Commissioner and Additional Commissioners of State Tax. In rejecting a challenge to this notification, the High Court held that:

“39. As pointed out by the Supreme Court in the case of Sahni Silk Mills [internal citation omitted], the courts should normally be rigorous while requiring the power to be exercised by the persons or the bodies authorized by the statutes. As noted above, it is essential that the delegated power should be exercised by the authority upon whom it is conferred and by no one else. At the same time, in the present administrative setup, the extreme judicial aversion to delegation should not be carried to an extreme. There is only one Commissioner of State Tax in the State of Gujarat, and having regard to the enormous functions and duties to be discharged under the new tax regime, he has been empowered to delegate his powers to the Special Commissioner of State Tax and the Additional Commissioners of State Tax.

40. We take notice of the fact that the delegation has been authorized expressly under Section 5(3) of the Act. We would have definitely interfered if the Special Commissioner or the Additional Commissioners would have further delegated the power to officers subordinate to them. Such is not the case over here.

41. In the impugned notification it has been stated that the functions delegated shall be under the overall supervision of the Commissioner. When the Commissioner stated that his functions were delegated subject to his overall supervision, it did not mean or should not be construed as if he reserved to himself the right to intervene to impose his own decision upon his delegate. The words in the last part of the impugned notification would mean that the Commissioner could control the exercise administratively as to the kinds of cases in which the delegate could take action. In other words, the administrative side of the delegate's duties were to be the subject of control and revision but not the essential power to decide, whether to take action or not in a particular case. Once the powers are delegated for the purpose of Section 69 of the Act, the subjective satisfaction, or rather, the reasonable belief should be that of the delegated authority.”

(emphasis supplied)

D Analysis

39 The essence of the present case lies in how the power to order a provisional attachment under Section 83 of the HPGST Act is construed. Before interpreting it, the provision is extracted below for convenience of reference:

“83. Provisional attachment to protect revenue in certain cases. - (1) Where during the pendency of any proceedings under section 62 or section 63 or section 64 or section 67 or section 73 or section 74, the Commissioner is of the opinion that for the purpose of protecting the interest of the Government revenue, it is necessary so to do, he may, by order in writing attach provisionally any property, including bank account, belonging to the taxable person in such manner as may be prescribed.

(2) Every such provisional attachment shall cease to have effect after the expiry of a period of one year from the date of the order made under sub-section (1).”

40 The marginal note to Section 83 provides some indication of Parliamentary intent. Section 83 provides for “provisional attachment to protect revenue in certain cases”. The first point to note is that the attachment is provisional – provisional in the sense that it is in aid of something else. The second point to note is that the purpose is to protect the revenue. The third point is the expression “in certain cases” which shows that in order to effect a provisional attachment, the conditions which have been spelt out in the statute must be fulfilled. Marginal notes, it is well-settled, do not control a statutory provision but provide some guidance in regard to content. Put differently, a marginal note indicates the drift of the provision. With these prefatory comments, the judgment must turn to the essential task of statutory construction. The language of the statute has to be interpreted bearing in mind that it is a taxing statute which comes up for interpretation. The provision must be construed on its plain terms. Equally, in interpreting the statute, we must have regard to the purpose underlying the provision. An interpretation which effectuates the purpose must be preferred particularly when it is supported by the plain meaning of the words used.

41 Sub-Section (1) of Section 83 can be bifurcated into several parts. The first part provides an insight on when in point of time or at which stage the power can be exercised. The second part specifies the authority to whom the power to order a provisional attachment is entrusted. The third part defines the conditions which must be fulfilled to validate the power or ordering a provisional attachment. The fourth part indicates the manner in which an attachment is to be leveled. The final and the fifth part defines the nature of the property which can be attached. Each of these special divisions which have been explained above is for convenience of exposition. While they are not watertight compartments, ultimately and together they aid in validating an understanding of the statute.

Each of the above five parts is now interpreted and explained below:

(i) The power to order a provisional attachment is entrusted during the pendency of proceedings under any one of six specified provisions: Sections 62, 63, 64, 67, 73 or 74. In other words, it is when a proceeding under any of these provisions is pending that a provisional attachment can be ordered;

(ii) The power to order a provisional attachment has been vested by the legislature in the Commissioner;

(iii) Before exercising the power, the Commissioner must be “of the opinion that for the purpose of protecting the interest of the government revenue, it is necessary so to do”;

(iv) The order for attachment must be in writing;

(v) The provisional attachment which is contemplated is of any property including a bank account belonging to the taxable person; and

(vi) The manner in which a provisional attachment is levied must be specified in the rules made pursuant to the provisions of the statute.

42 Under sub-Section (2) of Section 83, a provisional attachment ceases to have effect upon the expiry of a period of one year of the order being passed under sub-Section (1). The power to levy a provisional attachment has been entrusted to the Commissioner during the pendency of proceedings under Sections 62, 63, 64, 67, 73 or as the case may be, Section 74. Section 62 contains provisions for assessment for non-filing of returns. Section 63 provides for assessment of unregistered persons. Section 64 contains provisions for summary assessment. Section 67 elucidates provisions for inspection, search and seizure. Before we dwell on Section 74, it would be material to note the provisions of Section 70 which are extracted below:

“70. Power to summon persons to give evidence and produce documents. - (1) The proper officer under this Act shall have powers to summon any person whose attendance he considers necessary either to give evidence or to produce a document or any other thing in any inquiry in the same manner, as provided in the case of a civil court under the provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, (5 of 1908).

(2) Every such inquiry referred to in sub-section (1) shall be deemed to be a "judicial proceedings" within the meaning of section 193 and section 228 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, (45 of 1860).”

43 A power is conferred by Section 70 upon the proper officer to summon a person whose attendance is considered necessary to give evidence or produce a document or any other things in any enquiry in the manner which is provided in the case of a civil court under the CPC.

44 Section 74 is extracted below:

“74. Determination of tax not paid or short paid or erroneously refunded or input tax credit wrongly availed or utilised by reason of fraud or any wilful mis-statement or suppression of facts. –

(1) Where it appears to the proper officer that any tax has not been paid or short paid or erroneously refunded or where input tax credit has been wrongly availed or utilised by reason of fraud, or any wilful mis-statement or suppression of facts to evade tax, he shall serve notice on the person chargeable with tax which has not been so paid or which has been so short paid or to whom the refund has erroneously been made, or who has wrongly availed or utilised input tax credit, requiring him to show cause as to why he should not pay the amount specified in the notice alongwith interest payable thereon under section 50 and a penalty equivalent to the tax specified in the notice.

(2) The proper officer shall issue the notice under sub-section (1) at least six months prior to the time limit specified in sub-section (10) for issuance of order.

(3) Where a notice has been issued for any period under sub-section (1), the proper officer may serve a statement, containing the details of tax not paid or short paid or erroneously refunded or input tax credit wrongly availed or utilised for such periods other than those covered under subsection (1), on the person chargeable with tax.

(4) The service of statement under sub-section (3) shall be deemed to be service of notice under sub-section (1) of section 73, subject to the condition that the grounds relied upon in the said statement, except the ground of fraud, or any wilful mis-statement or suppression of facts to evade tax, for periods other than those covered under sub-section (1) are the same as are mentioned in the earlier notice.

(5) The person chargeable with tax may, before service of notice under sub-section (1), pay the amount of tax alongwith interest payable under section 50 and a penalty equivalent to fifteen per cent of such tax on the basis of his own ascertainment of such tax or the tax as ascertained by the proper officer and inform the proper officer in writing of such payment.

(6) The proper officer, on receipt of such information, shall not serve any notice under sub-section (1), in respect of the tax so paid or any penalty payable under the provisions of this Act or the rules made thereunder.

(7) Where the proper officer is of the opinion that the amount paid under sub-section (5) falls short of the amount actually payable, he shall proceed to issue the notice as provided for in sub-section (1) in respect of such amount which falls short of the amount actually payable.

(8) Where any person chargeable with tax under sub-section (1) pays the said tax alongwith interest payable under section 50 and a penalty equivalent to twenty five per cent of such tax within thirty days of issue of the notice, all proceedings in respect of the said notice shall be deemed to be concluded.

(9) The proper officer shall, after considering the representation, if any, made by the person chargeable with tax, determine the amount of tax, interest and penalty due from such person and issue an order.

(10) The proper officer shall issue the order under sub-section (9) within a period of five years from the due date for furnishing of annual return for the financial year to which the tax not paid or short paid or input tax credit wrongly availed or utilised relates to or within five years from the date of erroneous refund.

(11) Where any person served with an order issued under sub-section (9) pays the tax along with interest payable thereon under section 50 and a penalty equivalent to fifty per cent of such tax within thirty days of communication of the order, all proceedings in respect of the said notice shall be deemed to be concluded.

Explanation-1. - For the purposes of section 73 and this section,-

(i) the expression "all proceedings in respect of the said notice" shall not include proceedings under section 132; and

(ii) where the notice under the same proceedings is issued to the main person liable to pay tax and some other persons, and such proceedings against the main person have been concluded under section 73 or section 74, the proceedings against all the persons liable to pay penalty under sections 122, 125, 129 and 130 are deemed to be concluded.

Explanation-2. - For the purpose of this Act, the expression "suppression" shall mean non-declaration of facts or information which a taxable person is required to declare in the return, statement, report or any other document furnished under this Act or the rules made thereunder, or failure to furnish any information on being asked for, in writing, by the proper officer.”

45 Sub- Section (1) of Section 74 empowers the proper officer to serve a notice on a person chargeable with tax where it appears that

(i) Any tax has not been paid;

(ii) Tax has been short paid;

(iii) Tax has been erroneously refunded; or

(iv) Input tax credit has been wrongly availed or utilized by reason of fraud, willful statement or suppression of fact to evade tax.

46 Sub-Section (1) enables the proper officer to issue a notice to show cause for the recovery of tax, interest payable under Section 50 and the penalty equivalent to the amount of tax specified in the notice. Sub-Sections (2), (3) and (4) lay down procedural provisions which are to be followed by the proper officer.

Secondly, under sub-Section (5) of Section 74, before the service of a notice under sub-Section (1), the person who is chargeable with tax may pay the tax together with interest and a penalty equivalent to fifteen per cent of the tax on the basis of their own ascertainment of the tax or as ascertained by the proper officer and inform the proper officer of the payment having been made upon receipt of the information. Sub-Section (6) stipulates that the proper officer shall not serve any notice under sub-Section (1) in respect of the tax so paid or any penalty payable under the provisions of the Act or the Rules.

47 On the other hand, when the proper officer is of the opinion that the amount which has been paid under sub-Section (5) falls short of the amount which is actually payable, a notice under sub-Section (1) is to issue for the amount which falls short of what is actually payable. Sub-Section (8) contains a stipulation that where a person who is chargeable with tax under sub-Section (1) pays the tax together with interest and a penalty of twenty-five per cent of the tax within thirty days of the issuance of the notice, all proceedings in respect of the notice shall be deemed to be concluded. Under sub-Section (9), the proper officer after considering the representation of the person chargeable to tax is authorized to determine the amount of tax, interest and penalty due and to issue an order. A period of five years is stipulated by sub-Section (10) for the issuance of an order in sub-Section (9). Sub-Section (11) stipulates that upon service of an order under sub-Section (9), all proceedings in respect of the notice shall be deemed to be concluded upon the person paying the tax with interest under Section 50 and a penalty equivalent to 50 per cent of the tax within thirty days of the communication of an order. These provisions indicate how sub-Sections (5), (8) and (11) operate at different stages of the process.

48 Now in this backdrop, it becomes necessary to emphasize that before the Commissioner can levy a provisional attachment, there must be a formation of “the opinion” and that it is necessary “so to do” for the purpose of protecting the interest of the government revenue. The power to levy a provisional attachment is draconian in nature. By the exercise of the power, a property belonging to the taxable person may be attached, including a bank account. The attachment is provisional and the statute has contemplated an attachment during the pendency of the proceedings under the stipulated statutory provisions noticed earlier. An attachment which is contemplated in Section 83 is, in other words, at a stage which is anterior to the finalization of an assessment or the raising of a demand.

Conscious as the legislature was of the draconian nature of the power and the serious consequences which emanate from the attachment of any property including a bank account of the taxable person, it conditioned the exercise of the power by employing specific statutory language which conditions the exercise of the power. The language of the statute indicates first, the necessity of the formation of opinion by the Commissioner; second, the formation of opinion before ordering a provisional attachment; third the existence of opinion that it is necessary so to do for the purpose of protecting the interest of the government revenue; fourth, the issuance of an order in writing for the attachment of any property of the taxable person; and fifth, the observance by the Commissioner of the provisions contained in the rules in regard to the manner of attachment. Each of these components of the statute are integral to a valid exercise of power. In other words, when the exercise of the power is challenged, the validity of its exercise will depend on a strict and punctilious observance of the statutory pre-conditions by the Commissioner. While conditioning the exercise of the power on the formation of an opinion by the Commissioner that "for the purpose of protecting the interest of the government revenue, it is necessary so to do", it is evident that the statute has not left the formation of opinion to an unguided subjective discretion of the Commissioner. The formation of the opinion must bear a proximate and live nexus to the purpose of protecting the interest of the government revenue.

49 By utilizing the expression "it is necessary so to do" the legislature has evinced an intent that an attachment is authorized not merely because it is expedient to do so (or profitable or practicable for the revenue to do so) but because it is necessary to do so in order to protect interest of the government revenue. Necessity postulates that the interest of the revenue can be protected only by a provisional attachment without which the interest of the revenue would stand defeated. Necessity in other words postulates a more stringent requirement than a mere expediency. A provisional attachment under Section 83 is contemplated during the pendency of certain proceedings, meaning thereby that a final demand or liability is yet to be crystallized. An anticipatory attachment of this nature must strictly conform to the requirements, both substantive and procedural, embodied in the statute and the rules. The exercise of unguided discretion cannot be permissible because it will leave citizens and their legitimate business activities to the peril of arbitrary power. Each of these ingredients must be strictly applied before a provisional attachment on the property of an assesses can be levied. The Commissioner must be alive to the fact that such provisions are not intended to authorize Commissioners to make preemptive strikes on the property of the assessee, merely because property is available for being attached. There must be a valid formation of the opinion that a provisional attachment is necessary for the purpose of protecting the interest of the government revenue.

50 These expressions in regard to both the purpose and necessity of provisional attachment implicate the doctrine of proportionality. Proportionality mandates the existence of a proximate or live link between the need for the attachment and the purpose which it is intended to secure. It also postulates the maintenance of a proportion between the nature and extent of the attachment and the purpose which is sought to be served by ordering it. Moreover, the words embodied in sub-Section (1) of Section 83, as interpreted above, would leave no manner of doubt that while ordering a provisional attachment the Commissioner must in the formation of the opinion act on the basis of tangible material on the basis of which the formation of opinion is based in regard to the existence of the statutory requirement. While dealing with a similar provision contained in Section 45 (Section 45 (1) provides as follows:

“45. Provisional attachment. - (1) Where during the tendency of any proceedings of assessment or reassessment of turnover escaping assessment, the Commissioner is of the opinion that for the purpose of protecting the interest of the Government revenue, it is necessary so to do, he may by order in writing attach provisionally any property belonging to the dealer in such manner as may be prescribed.”) of the Gujarat Value Added Tax Act 2003, one of us (Hon’ble Mr Justice MR Shah) speaking for a Division Bench of the Gujarat High Court in Vishwanath Realtor v State of Gujarat Special Civil No. 7210 of 2015, decided on 29 April 2015 observed:

“8.3. Section 45 of the VAT Act confers powers upon the Commissioner to pass the order of provisional attachment of any property belonging to the dealer during the pendency of any proceedings of assessment or reassessment of turnover escaping assessment. However, the order of provisional attachment can be passed by the Commissioner when the Commissioner is of the opinion that for the purpose of protecting the interest of the Government Revenue, it is necessary so to do. Therefore, before passing the order of provisional attachment, there must be an opinion formed by the Commissioner that for the purpose of protecting the interest of the Government Revenue during the pendency of any proceedings of assessment or reassessment, it is necessary to attach provisionally any property belonging to the dealer.

However, such satisfaction must be on some tangible material on objective facts with the Commissioner. In a given case, on the basis of the past conduct of the dealer and on the basis of some reliable information that the dealer is likely to defeat the claim of the Revenue in case any order is passed against the dealer under the VAT Act and/or the dealer is likely to sale his properties and/or sale and/or dispose of the properties and in case after the conclusion of the assessment/reassessment proceedings, if there is any tax liability, the Revenue may not be in a position to recover the amount thereafter, in such a case only, however, on formation of subjective satisfaction/opinion, the Commissioner may exercise the powers under Section 45 of the VAT Act.”

(emphasis supplied)

51 We adopt the test of the existence of “tangible material”. In this context, reference may be made to the decision of this Court in the Commissioner of Income Tax v Kelvinator of India Limited (2010) 2 SCC 723. Mr Justice SH Kapadia (as the learned Chief Justice then was) while considering the expression "reason to believe" in Section 147 of the Income Tax Act 1961 that income chargeable to tax has escaped assessment inter alia by the omission or failure of the assessee to disclose fully and truly all material facts necessary for the assessment of that year, held that the power to reopen an assessment must be conditioned on the existence of “tangible material” and that “reasons must have a live link with the formation of the belief”. This principle was followed subsequently in a two judge Bench decision in Income Tax Officer, Ward No. 162 (2) v Techspan India Private Limited (2018) 6 SCC 685. While adverting to these decisions we have noticed that Section 83 of the HPGST Act uses the expression “opinion” as distinguished from “reasons to believe”. However for the reasons that we have indicated earlier we are clearly of the view that the formation of the opinion must be based on tangible material which indicates a live link to the necessity to order a provisional attachment to protect the interest of the government revenue.

52 Rule 159 prescribes modalities for effecting a provisional attachment of property. Rule 159 provides thus :

“159. Publication of information in respect of persons in certain cases. - (1) If the Commissioner, or any other officer authorised by him in this behalf, is of the opinion that it is necessary or expedient in the public interest to publish the name of any person and any other particulars relating to any proceedings or prosecution under this Act in respect of such person, it may cause to be published such name and particulars in such manner as it thinks fit.

(2) No publication under this section shall be made in relation to any penalty imposed under this Act until the time for presenting an appeal to the Appellate Authority under section 107 has expired without an appeal having been presented or the appeal, if presented, has been disposed of.

Explanation. - In the case of firm, company or other association of persons, the names of the partners of the firm, directors, managing agents, secretaries and treasurers or managers of the company, or the members of the association, as the case may be, may also be published if, in the opinion of the Commissioner, or any other officer authorised by him in this behalf, circumstances of the case justify it.”

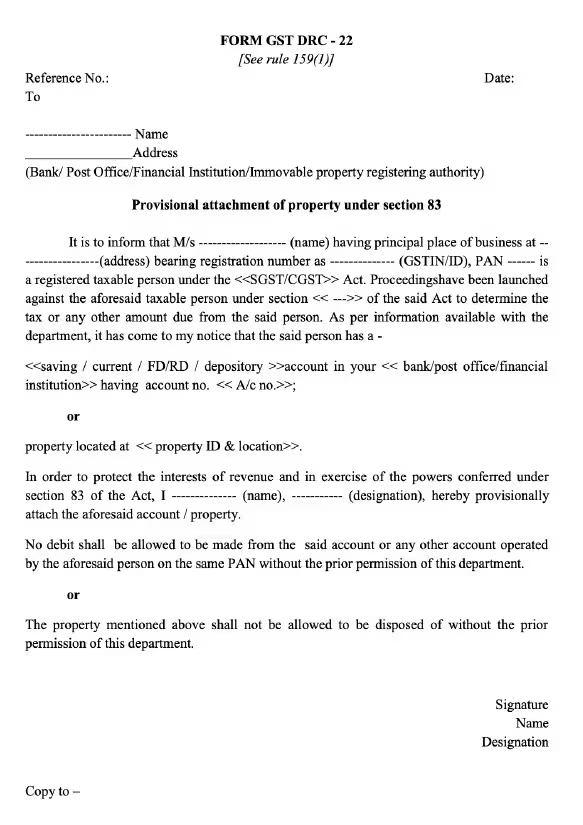

53 Under sub-Rule (1) of Rule 159, an attachment of property by the Commissioner under Section 83 is effected by passing an order mentioning the details of the property which is attached. The form in which the order is to be made is prescribed in form GST DRC-22. This form is extracted below:

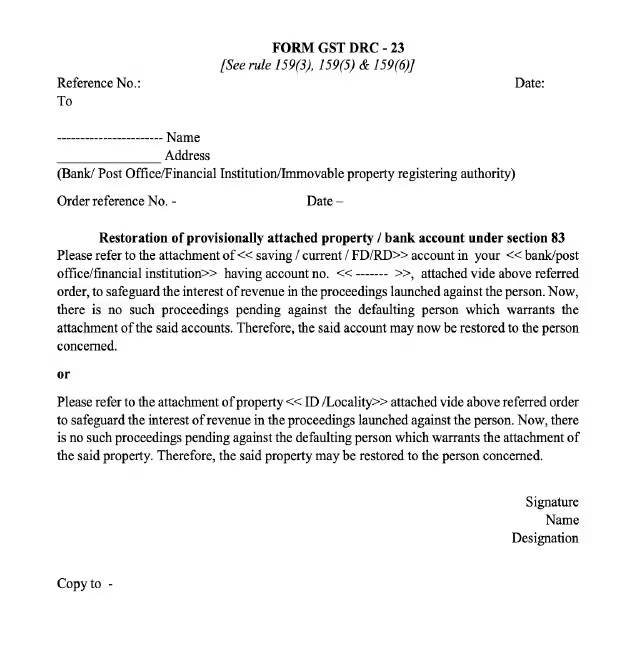

54 Under sub-Rule (5) of Rule 159, the person whose property is attached is allowed seven days’ time to file an objection that the property attached “was or is not liable to attachment”. Sub-Rule (5) stipulates that the Commissioner may “after affording an opportunity of being heard to the person filing the objection” release the property by an order in form GSTDRC-23. Similarly, under sub-Rule (6) upon being satisfied that the property was or is no longer liable to be attached, the Commissioner is empowered to release the property by issuing an order in Form GST DRC- 23 for the releasing of the property under attachment. The Form is extracted below :

55 A significant aspect of Rule 159(5) is that upon the levy of a provisional attachment, the person whose property is attached is empowered to file an objection within seven days on the ground that the property was or is not liable to attachment. In using the expression “was or is no longer liable for attachment”, the delegate of the legislature has comprehended two alternative situations. The first, evidenced by the use of the words “was” indicates that the property was on the date of the attachment in the past not liable to be attached. That is the reason for the use of the past tense “was”. The expression “is not liable to attachment indicates a situation in praesenti. Even if the property, arguably, was validly attached in the past, the person whose property has been attached may demonstrate to the Commissioner that it is not liable to be attached in the present.

56 The second significant aspect of sub-Rule (5) is the mandatory requirement of furnishing an opportunity of being heard to the person whose property is attached. This is in consonance with the principles of natural justice and ensures that a fair procedure is observed. Sub-Rule (5) provides for a post- provisional attachment right of:

(i) Submitting an objection to the attachment;

(ii) An opportunity of being heard.

Sub - Rule (5) contains clear language to the effect that a person whose property is attached is entitled to two procedural entitlements: first, the right to submit an objection on the ground that the property was not or is not liable to be attached; and second, an opportunity of being heard to the person filing an objection. This is a clear indicator that in addition the filing of an objection, the person whose property is attached is entitled to an opportunity of being heard. It is not open to the Commissioner, as has been stated in the present case, to hold the view that the only safeguard under sub-Rule 5 is to submit an objection without an opportunity of a personal hearing. Such a construction would be plainly contrary to sub-Rule 5 which contemplates both the submission of an objection to the attachment and an opportunity of being heard. The opportunity of being heard can be availed of as a matter of right by the person whose property is attached.

Both the right to submit an objection and to be afforded an opportunity of being heard are valuable safeguards. The consequence of a provisional attachment is serious. It displaces the person whose property is attached from dealing with the property. Where a bank account is attached, it prevents the person from operating the account. A business entity whose bank account is attached is seriously prejudiced by the inability to utilize the proceeds of the account for the purpose of business. The dual procedural safeguards inserted in sub-Rule 5 of Rule 159 demand strict compliance.

The Commissioner who hears the objections must pass a reasoned order either accepting or rejecting the objections. To allow the Commissioner to get by without passing a reasoned order will make his decision subjective and defeat the purpose of subjecting it to judicial scrutiny. The Commissioner must deal with the objections and pass a reasoned order indicating whether, and if not, why the objections are not being accepted. Sub- Rule 6 of Rule 159 allows for the release of a property which either was or is no longer liable for attachment. The form in which such an order has to be passed, namely form GST DRC-23, states that “now there is no such proceeding pending against the defaulting person which warrants attachment” of the account or as the case may be, the property. Sub-Rules 5 and 6 do not expressly contemplate a situation in which the person whose property is attached can object on the ground that the attachment is in excess of the amount likely to be due for which proceedings have been launched under the Act. Nor does it provide for a specific opportunity to the taxable person to offer any alternative form of security in lieu of the attachment. Such an opportunity must be read in to the provision to allow for a fair working in practice.

Whether any alternative security that is furnished by the taxable person should be accepted and if so, its sufficiency, is a matter for the Commissioner to determine.

Undoubtedly, the taxable person may not have a right to demand that only a particular form of security must be accepted. The Commissioner has to decide whether the form of security offered would secure the interest of the revenue.

Where the taxable person sets up the plea that the extent of the attachment is excessive or where the taxable person offers an alternative form of security, these are also matters which ought to be determined by the Commissioner in the exercise of powers under Rule 159(5). The scope of objection can also extend to the nature of the property which is being provisionally attached.

Now, it is in this backdrop that we proceed to a determination of whether the petition under Article 226 was maintainable and if it was, whether Commissioner exercised the powers under Section 83 read with Rule 159 in accordance with law.

57 The material facts for making this determination need to be recapitulated.

On 3 October 2018, a memo was issued under Section 70 (incorrectly referring to the provisions of Section 74) by the Joint Commissioner of State Taxes and Excise directing the appellant to appear on 9 October 2018 along with specific documents pertaining to the yea₹ 2017-18 and 2018-19. The notice stated that in the event that the appellant failed to appear, the Commissioner would be constrained to issue a notice to show cause under Section 74(1). On 9 October 2018, two partners of the appellant attended the hearing. On 10 October 2018, a ‘detection case’ under Section 74 of the HPGST Act and CGST Act read with Section 20 of the IGST Act was initiated against a supplier of the appellant, GM Power Tech by a search and seizure operation conducted under Section 67. On 15 October 2018, the partners of the appellant attended the case hearing and provided certain documents which were required by the department. The partners of GM Powertech were arrested under the provisions of Sections 69 and 132 of the HPGST Act on 3 December 2018, on the allegation that they had made fraudulent claims of ITC from fake/fictitious firms of Delhi and Kanpur. On 15 December 2018, the representatives of the appellant were directed to remain present on 17 December 2018 for explaining the allegedly illegal claim of ITC for 2017-18 and 2018-19. A representative of the appellant attended the enquiry on 17 December 2018. On 9 January 2019, an order of provisional attachment was issued under Section 83 by the Joint Commissioner of State Taxes and Excise by which a payment of ₹ 5 crores due to the appellant from M/s Fujikawa Power was attached on the ground that the appellant had availed of ITC of ₹ 3.25 crores against the purchase of goods valued at about ₹ 21 crores from GM Powertech for 2017-18 and 2018-19 and a case of GST fraud had been instituted against the alleged supplier. On 19 January 2019, Form GST DRC-22 was issued to Fujikawa Power regarding the attachment of ₹ 5 crores. On 29 January 2019, the appellant made a representation under Rule 159(5) for unblocking the credit and releasing the amount which was provisionally attached.

On 30 January 2019, the order of provisional attachment was withdrawn completely with immediate effect. On 9 April 2019 and 5 July 2019 a representative of the appellant attended the case hearing. On 4 July 2020, an intimation was furnished to the appellant of the tax ascertained as payable under Section 74(5). According to the intimation, the appellant received among other items, lead ingots from GM Powertech during FY 2017-18 and 2018-19 and investigation had revealed that ITC had been fraudulently availed of by the supplier on the basis of the invoices of fake firms. The appellant had also availed of ITC due to inward supplies from GM Powertech. On 3 and 5 August 2020, the appellant filed its submissions under Rule 142(2) (a) against the proposed liability. On 6 October 2020, an order was passed under Section 74(9) against GM Powertech confirming a demand of ₹ 39.48 crores for 2017-18 and 2018-19. The proceedings concluded that GM Powertech had

(i) No business establishment or property in Himachal Pradesh; and

(ii) No security or surety.

58 On 21 October 2020, the Commissioner of State Taxes and Excise, Himachal Pradesh delegated, in pursuance of the provisions of Section 5(3) the powers vested under Section 83(1) inter alia to the Joint Commissioner of State Taxes and Excise. On 28 October 2020, a fresh order was issued under Section 83 stating that proceedings were initiated against the appellant under Section 74 since it was found to be involved in an ITC fraud of ₹ 5.03 crores during 2017-18 and 2018-19. Since a GST fraud case had been initiated against GM Powertech on whom a demand had been raised, the ITC claimed by the appellant against supplies effected by GM Powertech was held to be inadmissible resulting in a provisional attachment of the payments due to the appellant to the extent of ₹ 5,03,82,554/-. A similar order was issued on 28 October 2020 under Section 83 to M/s Deepak International Limited. The appellant submitted a detailed representation under Rule 159 (5) to the Joint Commissioner. The representation was rejected on 6 November 2020 without affording an opportunity of being heard. Thereafter, on 27 November 2020, a notice to show cause was issued to the appellant under Section 74(1) recording that the appellant had shown inward supplies of lead ingots from GM Powertech and had claimed and utilized ITC on that basis. However, all suppliers from whom GM Powertech had shown inward supplies of goods were found to be fictitious, fake and non-existent. The GST registration of GM Powertech had been cancelled and by an order under Section 74(9), an additional demand of ₹ 39.48 crores was confirmed. The appellant was called upon to show cause as to why interest, tax and penalty should not be imposed. The appellant instituted writ proceedings before the Himachal Pradesh High Court inter alia for

(i) Challenging the delegation by the Commissioner on 21 October 2020;

(ii) The proceedings initiated under Section 83; and

(iii) Revocation of the provisional attachment.

The writ petition was dismissed by the High Court on the ground that the appellant had an alternative remedy available in law.